Access the essential membership for Modern Managers

The ability to plan ahead has always been important for organizations. However, rapid political, environmental and technological changes mean that long-term business forecasts are increasingly difficult to make. Scenario planning can help, by enabling organizations to model a series of potential futures, and to modify their future plans according to the most feasible scenarios.

What Is Scenario Planning?

Scenarios are not predictions but plausible, well-illustrated hypotheses of various ‘what if’ possibilities. The result of the scenario planning process is a set of stories that provide alternative views of what the future might look like.

Organizations can therefore use scenarios to help them visualize and imagine what may happen in the future. Developing the scenarios forces planners and policy-makers to face the uncertainties in the future and explore how the various scenarios might play out.

How Does it Differ From Business Continuity Management?

Scenario planning helps organizations look at the challenges they face from a different perspective, by identifying and analyzing current and future trends and considering how these trends may impact on their own organization.

Business Continuity Management (BCM) on the other hand, is a process that helps manage risks to the smooth running of an organization or delivery of a service. BCM planning is designed to enable the continuity of critical organizational functions in the event of a disruption, e.g. due to fire, flood, and to ensure effective recovery afterwards.

Who Should Use Scenario Planning?

Scenario planning is widely used by organizations who work with a long-term vision, such as local governments or energy companies. It is of less value for organizations operating in a rapidly changing environment, for example, technology companies. Scenarios take time and resources to frame, and sometimes the rate of change affecting an organization in the short-term is such that long-term planning is less viable.

Who’s Who in Scenario Planning?

Scenario planning has its roots in military strategic studies, but was transformed into a business tool in the 1970s by Royal Dutch/Shell. The scenarios they developed enabled Shell to maintain its competitive advantage during the oil crisis of 1973, and remain an important part of their strategy to date.

A former co-ordinator of scenarios at Royal Dutch/Shell, Arie de Geus, conducted a study of how large corporations can improve their prospects for survival. The ensuing book, The Living Company, revealed that most of the long-established organizations he studied had recognized the need for change at least once in their history. As a result, they were often able to identify new opportunities ahead of time. However, long-lived organizations are a distinct minority and de Geus concluded that the reason most large corporations die prematurely is because of an inability to learn, adapt and evolve as the world around them changes. [1]

According to de Geus organizations must constantly ask questions such as:

- Suppose x happened?

- How would we react?

- Suppose our competitors expanded?

- Suppose there was a change in government or a shift in technologies?

How Would We Respond to it All?

Another renowned scenario expert is Peter Schwartz. Schwartz worked for Shell for five years before starting up the Global Business Network in 1987. Scenario planning, Schwartz states, is primarily about protecting your company against an uncertain future. His book, The Art of the Long View, discusses the ways in which scenarios help encapsulate hopes, fears, dreams and beliefs into a visualization of the possible futures that lie ahead.

Schwartz argues that the future we arrive at will be determined in large part by how we mold perception. This perception will be based upon our own imaginative interpretations of what the future should look like. “Scenario thinking is an art not a science,” he says. [2]

Kees van der Heijden’s book, The Sixth Sense, is sometimes referred to as the scenario planning bible. Largely responsible for overseeing Royal Dutch/Shell’s experimentation with scenario planning, he believes that scenario thinking is becoming an increasingly important way of addressing problem solving, strategic communication and organizational decision-making, as well as organizational learning and development. [3]

Van der Heijden stresses that the ‘objective of rehearsing the future does not mean that scenarios seek to predict the future.’[4] Instead, he thinks of scenario planning as an ‘approach based on reasoning, research and real world observations’, and promotes scenario planning as an individual and organizational strategic thinking and learning process. [6]

The Scenario Planning Process

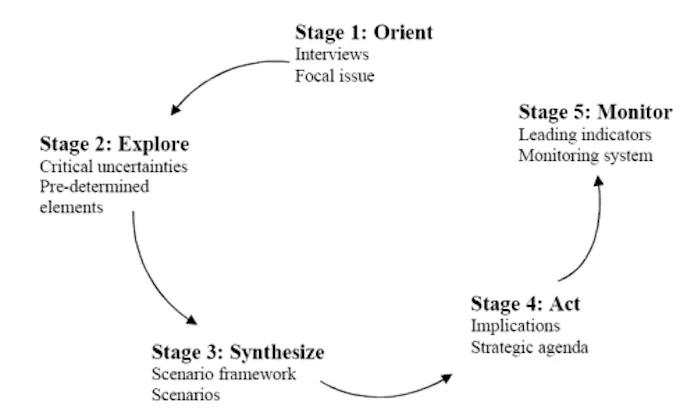

Scenario planning uses a basic five stage process as shown by the diagram designed by the Global Business Network below.

- Orient the process by holding structured interviews with key employees of the organization to determine the challenges faced by the organization, and any assumptions held about those challenge

- Explore the change drivers which might shape the future environment of an organization, such as economic changes, e.g. boom or recession periods, or demographic changes like an aging population.

- Synthesize in order to identify the two or three critical uncertainties, i.e. those drivers which have an uncertain impact on the future. This is a key part of scenario planning. Scenarios must be developed around drivers where the future impact is uncertain, rather than those which have a probable or certain impact, which may already be being dealt with in the here and now. ‘What if …’ questions can then be asked about the impact of these uncertainties, providing the basis for the scenarios.

- Act on the findings. This is where decisions are made about what to do about these possible future scenarios. Questions are asked such as:

- What if this scenario is the future?

- What actions can be taken today to prepare for it?

- Are there any actions that can be taken to create a more desirable future, or to move away from a negative one?

- Monitor the drivers. External drivers and trends change, and so scenarios may have to be adjusted as required. The monitoring system will also indicate if a particular scenario is beginning to emerge, allowing the actions agreed in stage four to begin to be implemented.

Why Use Scenario Planning?

It is easy for organizations to become so focused on their daily operations that they neglect the potential impact of external events on the running of their organization. By using scenario planning, however, organizations can step back from the day-to-day business and actively analyze how they function from a broader perspective.

Scenario planning can be particularly valuable where employees are encouraged to actively participate in the development of their organization. The involvement of employees from across the organization can result in a ‘cross-fertilization’ of passions and ideas which the structure of scenario planning can then harness. Members of such a group may well have useful ideas about the organization’s future direction but it is only when a scenario planning initiative is in place that this knowledge can be collated and put to good use. As well as the generation of the scenarios, the opportunity for employees to share knowledge can increase understanding of the way other areas of the organization operate and improve organizational networking and communication.

It is also a useful tool for integrating a progressive approach to uncertainty and risk into existing management styles. Decisions previously viewed as ‘risky’ become more informed once potential dangers and opportunities are identified, and existing plans and strategies can be held up against a range of scenarios to assess how robust they are.

Disadvantages of Scenario Planning

One of the principal disadvantages of scenario planning is the inability to know which, if any, of several possible futures will actually occur. The very nature of scenarios means that there is a degree of guesswork or assumption when formulating the scenarios, and so gaining agreement or consensus from all involved can be difficult. The creation of scenarios is also time-consuming and labor intensive.

A potential danger of scenario planning lies in the possibility that a particularly appealing scenario may unconsciously be taken as fact rather than a possibility, or indeed, an unfavorable or threatening scenario may be met with denial. Both of these reactions are natural, and providing the scenario planners remain aware of the possibility of this happening, a simple check that this hasn’t occurred may be all that’s required.

Scenarios don’t work for everyone. If an organization doesn’t have suitable time and resources, or the desire to embrace change is missing, scenario planning will add little value to the process of strategic planning. Further, those organizations which do not operate on a long-term scale will gain little from a scenario planning exercise.

Conclusion

Scenario planning is a flexible process that can be tailored to different circumstances, needs and organizations. For scenarios to be successful, they must be as detailed and diverse as possible, and capable of addressing the majority of possibilities. The more a strategy is capable of standing up against several different hypothetical futures, the more likely it is that it will endure actual future changes and events.

Scenario planning, as part of a larger planning process, can allow organizations to underpin their strategic decision-making with the knowledge that most plausible futures have been considered. The point is not to pick a preferred future and wait for it to happen, but to be sure that the organization’s strategy can stand up, whatever may happen.